Enactivism and Distributed Cognition

When people hear about cognition, it is often described as something that happens entirely in the brain. The traditional model treats the mind as a kind of computer: information goes in, gets processed, and produces an output.

When most people hear about cognition, it is often described as something that happens entirely in the brain (information goes in and gets processed). While this view has been useful, it overlooks important aspects of how humans think and learn.

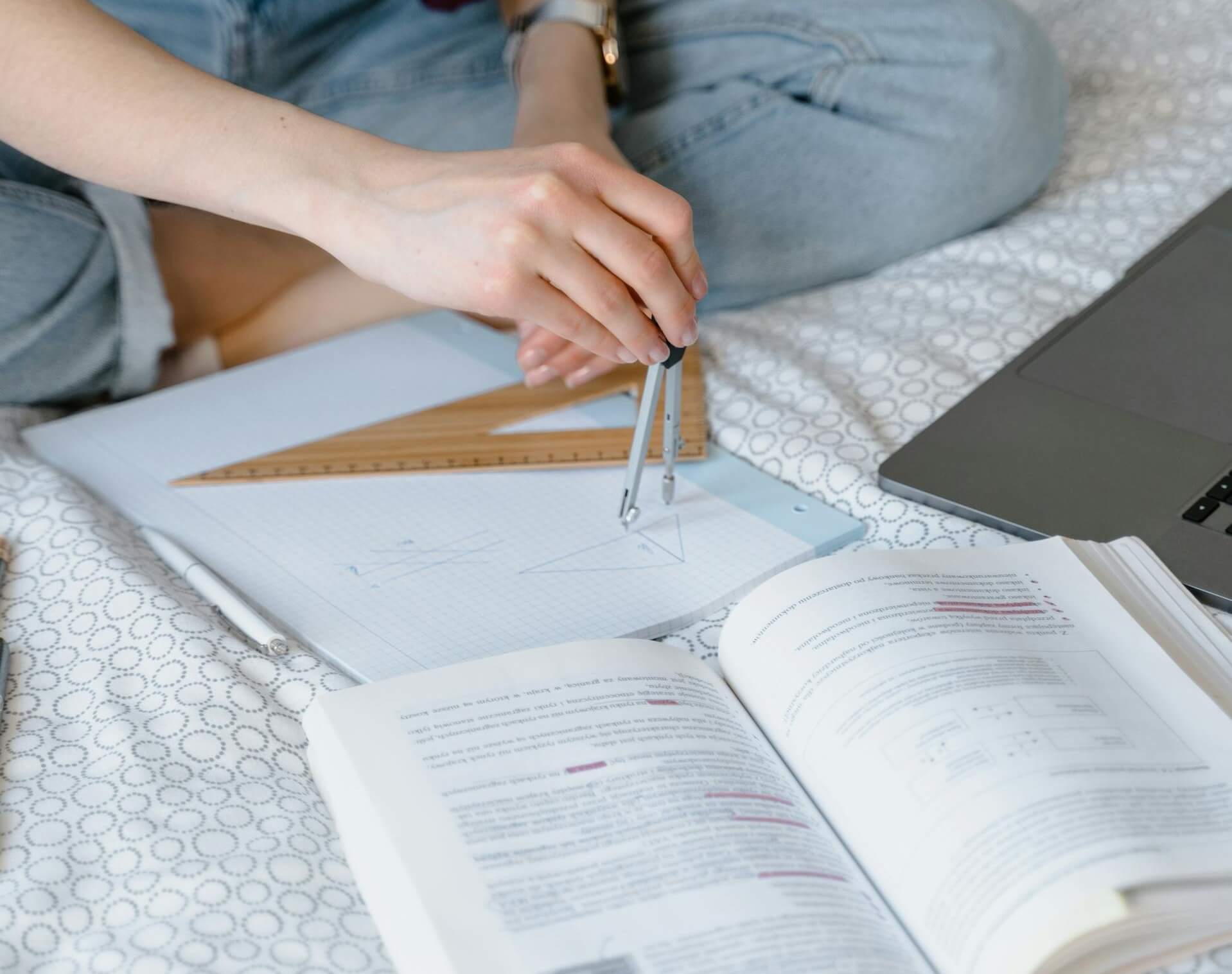

Take a child working through a math problem. They may count on their fingers, move objects around on the desk, or talk themselves through each step. These actions are part of the thinking process itself. If you suddenly stop the child from using their fingers, they may find it harder to continue because you’ve taken away one of the processes that support their thinking. From this simple scenario, we can say that cognition is not confined to the brain alone; it also involves and takes place through the other parts of the body and within the environment.

This perspective opens the door to two important concepts in cognitive science: Enactivism and Distributed Cognition. Enactivism emphasises that cognition emerges through active engagement with the world (through perception, movement, and interaction). Distributed Cognition expands on this idea further, suggesting that thinking is often shared across people, tools, and cultural systems. A notebook, a calculator, or a peer in discussion can all become part of the cognitive process.

Enactivism – Cognition expressed as Action

Enactivism is an evolving perspective in cognitive science, highlighting how a person’s bodily engagement and interaction with their surroundings shape their thinking and experiences. Developed in the 1990s as a critique of earlier theories that prioritised mental representations and computational models of the mind, enactivism shifts the focus toward lived, embodied processes.

From an enactive point of view, perception is not the brain building a picture of the world and then handing it over to the body; rather, it is the body moving, touching, listening, and seeing in constant interaction with the surroundings. A blind person using a cane does not “picture” the ground in their head. They feel the world through the cane, and their perception is directly shaped by that movement and the contact it provides.

This perspective also changes how we think about learning. A student learning about mass picks up objects of different weights, feels the resistance in their hands, compares which is heavier or lighter, and predicts what might happen if those objects are dropped or pushed. Through repeated experiences, they begin to notice patterns; a small stone feels close to 200 grams, a bag of rice is about 5 kilograms. Eventually, they can assign approximate numerical values just by looking at or lightly handling an object. Their ability to ‘estimate weight’ emerges from embodied interaction with the world, where direct sensory experience gradually links to abstract numerical concepts.

Enactivism draws our attention to the importance of embodied experience, practical engagement, and the ways learners actively construct meaning through action.

Distributed Cognition – Thinking Beyond the Individual

Distributed Cognition takes the enactive perspective a step further. It argues that cognition is not limited to the individual at all. Instead, thinking is often spread across people, tools, and environments. The unit of analysis then becomes the entire system in which thinking takes place.

Consider a pilot flying an aeroplane. The task is not accomplished by the pilot’s brain alone. It depends on a network of instruments, co-pilots, checklists, and communication systems. Together, these elements form a cognitive system. Remove one piece (say, the communication systems) and the ability to think and act effectively changes drastically.

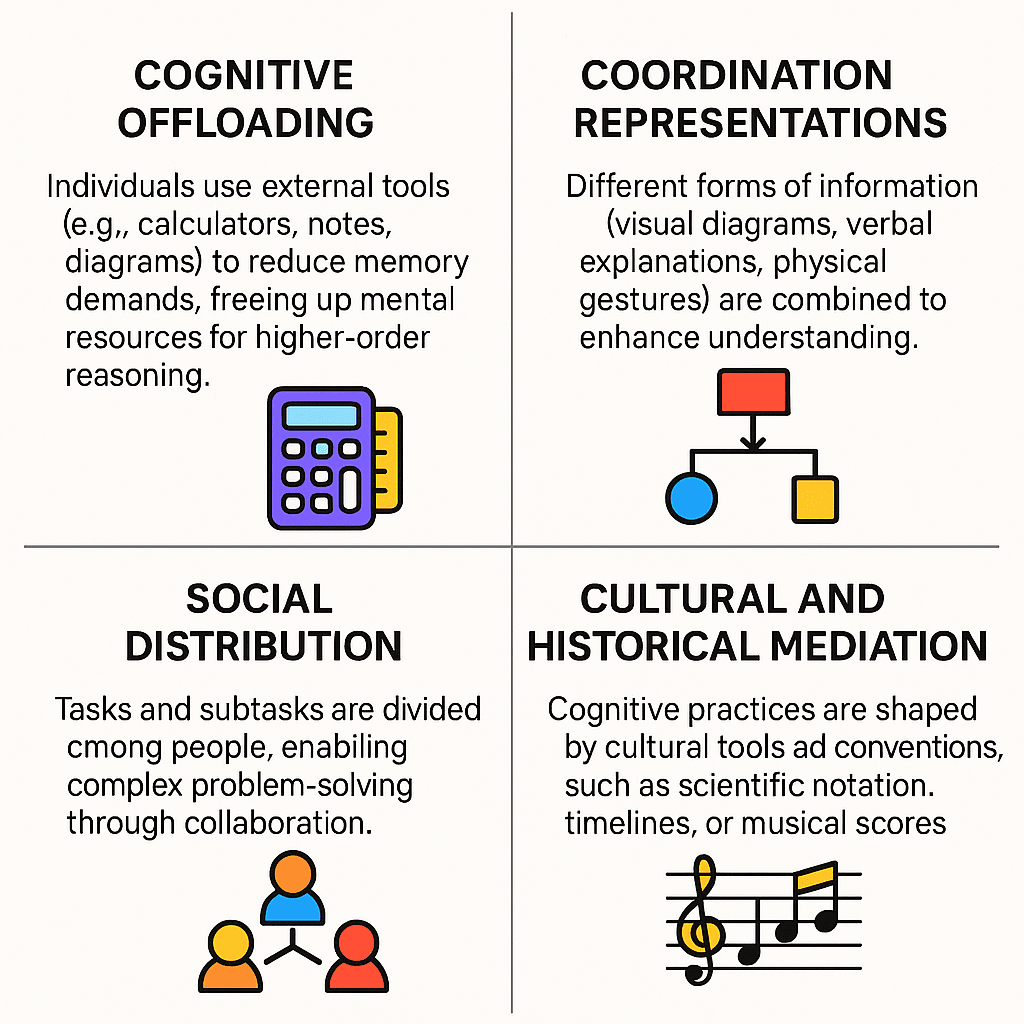

In everyday learning, the same principle applies. Students use calculators, diagrams, group discussions, and even classroom walls filled with posters as part of their cognitive process. The notebook is a tool that helps students understand what is being taught by offloading memory and allowing patterns to emerge. Similarly, collaboration with peers distributes the cognitive load, making it possible to solve problems that would be too complex for one student alone.

Practices like using number lines in math or concept maps in science are all tools that structure how students learn and reason. In this sense, thinking is never just an internal act; it is always situated within broader systems of tools, practices, and communities.

Distributed Cognition operates through several mechanisms:

Child Development as Expanding Cognitive Ecosystems

For children, development requires becoming adept at navigating and coordinating within broader cognitive systems. Growth, then, is marked by an increasing ability to flexibly integrate these external supports into one’s own problem-solving and sense-making processes.

Creating environments that foster this kind of development means designing spaces, tools, and interactions that lower barriers to participation and scaffold deeper engagement. Classrooms that encourage collaborative learning, digital platforms that make knowledge accessible, and cultural practices that invite children into meaningful roles all contribute to making learning easier and better. These environments extend cognitive capacity by allowing learners to share the load of thinking, experiment with different perspectives, and internalise effective strategies and habits.

Adiutor

Adiutor means "helper" - we do just that, by taking a load of your school administration and helping you focus on what matters most: the kids.

References

Clark, A. (1997). Being there: Putting brain, body, and world together again. MIT Press.

Clark, A., & Chalmers, D. (1998). The extended mind. Analysis, 58(1), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/analys/58.1.7

Hutchins, E. (1995). Cognition in the wild. MIT Press.

Hutchins, E. (2000). Distributed cognition. In International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences

Kirsh, D. (2010). Thinking with external representations. AI & Society, 25(4), 441–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-010-0272-8

Thelen, E., & Smith, L. B. (1994). A dynamic systems approach to the development of cognition and action. MIT Press.

Varela, F. J., Thompson, E., & Rosch, E. (1991). The embodied mind: Cognitive science and human experience. MIT Press.