What is Flow Theory?

Have you ever been so absorbed in something that time seemed to vanish? Maybe you were working, playing a game, learning, or even giving a good lecture where everything was clicking, and for a while, the rest of the world disappeared

Have you ever been so absorbed in something that time seemed to vanish? Maybe you were working, playing a game, learning, or even giving a good lecture where everything was clicking, and for a while, the rest of the world disappeared. That mental state is what psychologist Mihály Csikszentmihalyi famously called flow.

It represents a state in which attention, motivation, and performance are fully aligned. In this state, there is this feeling of a sense of control, clarity of purpose, and intrinsic satisfaction derived from the activity itself.

Conditions for Flow

The flow state develops under specific psychological and environmental conditions that align an individual’s attention, goals, and capabilities. Csikszentmihalyi identified several key components that consistently appear when people enter a state of flow:

Clear goals: The first and perhaps most fundamental condition is clear goals. Individuals need to know what they are working toward. In a classroom, this can be interpreted as defining a learning objective that is both specific and attainable. Clear goals help students focus their attention and measure their progress, creating a sense of direction and purpose throughout the activity.

Immediate feedback: This does not always need to come from an external source, such as a teacher. Sometimes, the activity itself provides feedback. A music student hearing the accuracy of a note as they practice or a math student getting a green tick after each solved question in an online quiz. Effective feedback loops reinforce engagement and sustain motivation.

Challenge and skill:

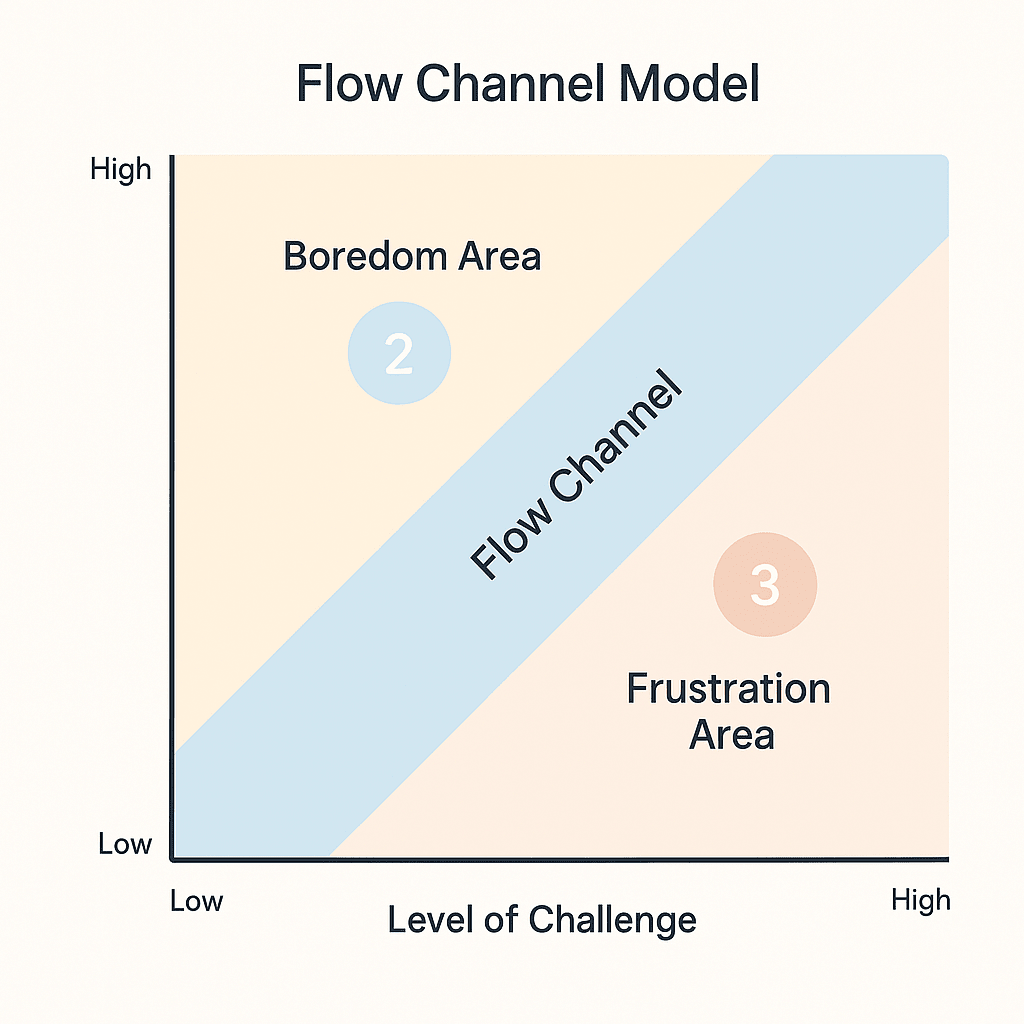

As learners progress through a task, maintaining a flow state depends on whether the level of challenge continues to rise in line with their growing skills. If the challenge remains too low while ability increases, learners enter the boredom area, where engagement declines, and they quickly lose interest. On the other hand, when a task’s difficulty exceeds the learner's current skill level, they enter the frustration area. In this state, the task may still hold interest, but the imbalance between challenge and ability leads to discouragement and reduced motivation. The aim, therefore, is to keep activities within the flow channel, where the challenge appropriately matches skill development, allowing both engagement and motivation to be sustained over time.

Focused attention: This is a level of concentration that minimises external distractions and internal noise is needed to achieve the flow mental state. Environments that support deep work (through structure, routine, and psychological safety) help learners enter and maintain this focused state.

Flow and Gamification

To harness this emotional engagement, many studies have examined how gamification (the application of game design principles to non-game contexts) can enhance learning outcomes in education. The central goal of gamification is to make learning more enjoyable, meaningful, and intrinsically rewarding.

In this context, the concept of flow aligns closely with gamified learning. Flow begins with clearly defined goals and concrete steps for achieving them. Well-designed games naturally foster a state of flow because they provide structured challenges, immediate feedback, and clear objectives that guide the player toward success. They also promote autonomy and give learners control over their progress. Adaptive learning systems that adjust difficulty based on performance (such as personalised quizzes or adaptive simulations) can keep learners consistently within their flow channel. These systems replicate what effective games do naturally. Thus, they evolve with the player’s ability, ensuring that boredom and frustration are minimised.

References

Choi, C., Mogami, T., & Medalia, A. (2007). Intrinsic motivation inventory: An adapted measure for schizophrenia research. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 36(5), 966–976. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbp030

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper & Row.

Hanus, M. D., & Fox, J. (2015). Assessing the effects of gamification in the classroom: A longitudinal study on intrinsic motivation, social comparison, satisfaction, effort, and academic performance. Computers & Education, 80, 152–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.08.019

Holyoke, L. B., & Larson, E. (2009). Engaging the adult learner: Creating effective learning experiences. Journal of Adult Education, 38(1), 13–22.

Liu, D., Santhanam, R., & Webster, J. (2017). Toward meaningful engagement: A framework for design and research of gamified information systems. MIS Quarterly, 41(4), 1011–1034. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2017/41.4.01

Moneta, G. B., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). The effect of perceived challenges and skills on the quality of subjective experience. Journal of Personality, 64(2), 275–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00512.x

Rawendy, D., Wardani, N. H., & Wibowo, A. P. (2017). Gamification for learning motivation: A review of literature. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology, 95(9), 1955–1965.