Self-Regulated Learning

Some students do not need to be told before they take action. They plan their study time, manage distractions, and remain motivated even when tasks become challenging. Others, equally capable, struggle to stay focused, forgetting deadlines or losing steam midway through. The difference between these two groups often comes down to self-regulation. Self-regulated learning refers to the ability of learners to take active control of their own learning processes, thus setting goals, managing their progress, and adjusting their strategies when needed. They engage in deliberate actions that help them plan, monitor, and evaluate their learning.

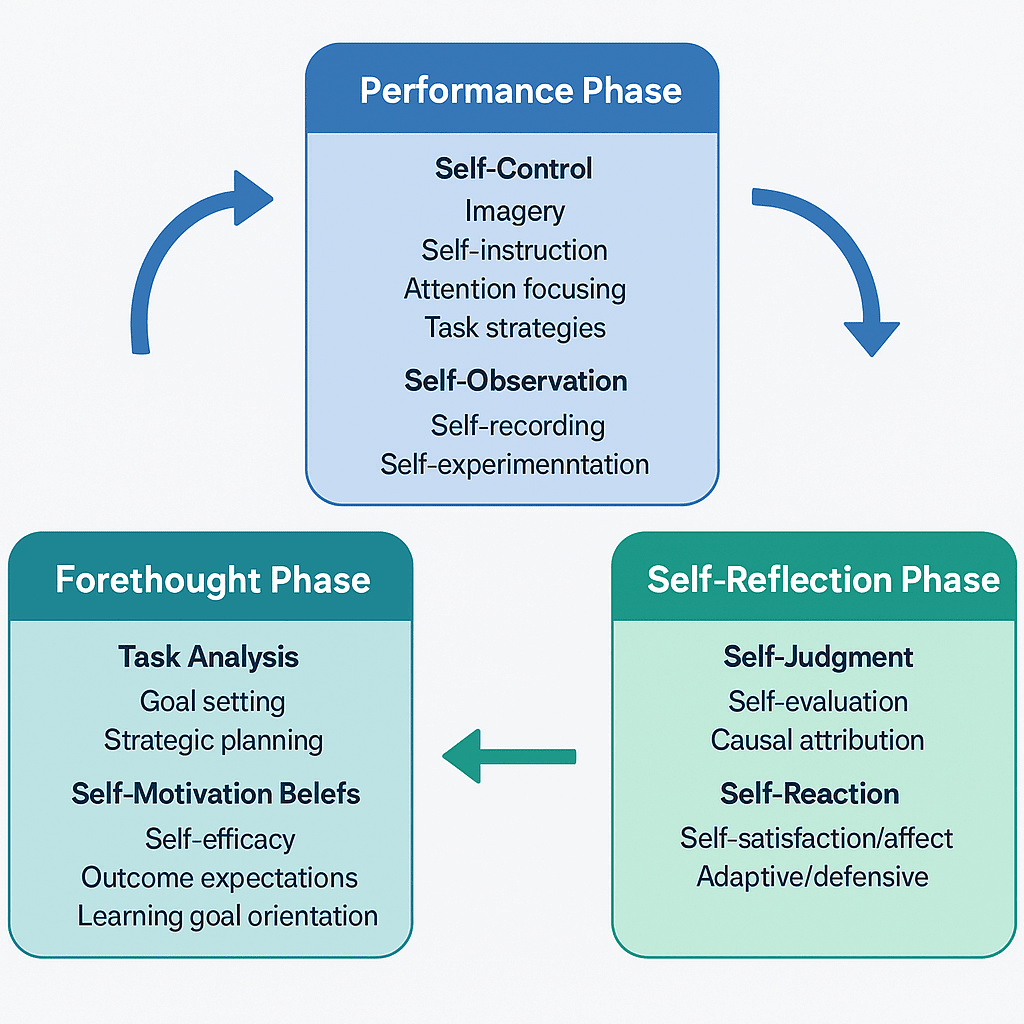

This theory, advanced notably by Barry Zimmerman and Dale Schunk, positions learning as a self-directed cycle involving three key phases: forethought (planning and goal setting), performance (strategy use and self-monitoring), and self-reflection (evaluation and adaptation). Through these phases, learners develop awareness of their cognitive processes, which supports deeper understanding and long-term retention.

Forethought – Learners plan and prepare before engaging in a task. This involves setting specific goals, selecting strategies, and forming beliefs about one’s ability to succeed (self-efficacy). For instance, before writing an essay, a student might decide to outline key arguments and set milestones for completion.

Performance – Learners implement their plans and monitor their progress while completing the task. Here, they need to have self-control (using strategies to stay on task) and self-observation (tracking attention, understanding, and time use).

Self-reflection – After completing the task, learners evaluate their performance and the effectiveness of their strategies. They consider questions like “What worked?” and “What could I do differently next time?” These reflections inform future forethought, creating a feedback loop that strengthens their learning processes over time.

According to this model, learners’ beliefs about their capabilities strongly influence their willingness to persist through challenges. While cognition and motivation occur internally, SRL is visible through behavioural actions that reflect deliberate control. Learners collaborate with peers or use external tools to support the goals they want to achieve. In this sense, self-regulated learning is also a set of observable actions that make learning more deliberate and efficient.

Development of Self-Regulated Learning

In the early stages, children rely heavily on instructions, schedules, and feedback, all of which are external structures provided by adults. Teachers and parents serve as regulators by setting expectations, modeling effective learning behaviors, and providing prompts that guide attention and effort. As time goes on, learners acquire self-regulatory skills as they interact with their environment, observe others, and experiment with different internalise.

As learners gain experience, they begin to internalise these strategies, developing the capacity to plan, monitor, and adjust their learning without constant guidance. This transition often occurs through situations where support is gradually reduced as learners demonstrate competence. By adolescence, students who have been encouraged to set goals, evaluate outcomes, and manage their motivation typically display stronger self-regulatory habits. Factors such as classroom environment, feedback quality, and prior beliefs about ability all influence how effectively learners acquire SRL skills.

Encouraging self-regulated learning (SRL) requires more than simply telling students to be independent. It involves deliberately designing learning environments and interactions that gradually build learners’ capacity to plan, monitor, and reflect on their own progress. In this, both educators and parents are central figures in shaping these conditions.

One of the most effective ways to support self-regulation is through explicit modelling. During problem solving, teachers or parents clearly demonstrate how they are approaching the problem to solve it. This can be done by thinking aloud while analysing a task and making decisions in a way the learner can understand. This modelling helps learners understand that learning requires active decision-making, evaluation, and adjustment. With time, learners internalise these thought patterns and begin to apply them independently.

Another way is to provide structured guidance that decreases as competence increases. Early on, learners may benefit from prompts or guided reflections that remind them to set goals or evaluate their understanding. As they develop, these supports can be gradually withdrawn, allowing learners to assume greater responsibility.

Adiutor

Adiutor means "helper" - we do just that, by taking a load of your school administration and helping you focus on what matters most: the kids.

References

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman.

Boekaerts, M., Pintrich, P. R., & Zeidner, M. (Eds.). (2000). Handbook of self-regulation. Academic Press.

Pajares, F. (2008). Motivational role of self-efficacy beliefs in self-regulated learning. In D. H. Schunk & B. J. Zimmerman (Eds.), Motivation and self-regulated learning: Theory, research, and applications (pp. 111–139). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 451–502). Academic Press.

Schunk, D. H., & Zimmerman, B. J. (1998). Self-regulated learning: From teaching to self-reflective practice. Guilford Press.

Schunk, D. H., & Zimmerman, B. J. (Eds.). (2012). Motivation and self-regulated learning: Theory, research, and applications. Routledge.

Winne, P. H., & Hadwin, A. F. (1998). Studying as self-regulated learning. In D. J. Hacker, J. Dunlosky, & A. C. Graesser (Eds.), Metacognition in educational theory and practice (pp. 277–304). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Zimmerman, B. J. (1989). A social cognitive view of self-regulated academic learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81(3), 329–339. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.81.3.329

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 13–39). Academic Press.

Zimmerman, B. J., & Schunk, D. H. (Eds.). (2011). Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance. Routledge.