Elaboration theory in the classroom

Charles Reigeluth’s Elaboration Theory offers a systematic framework, advocating a progression that begins with the simplest representation of a subject and gradually advances toward more complex forms.

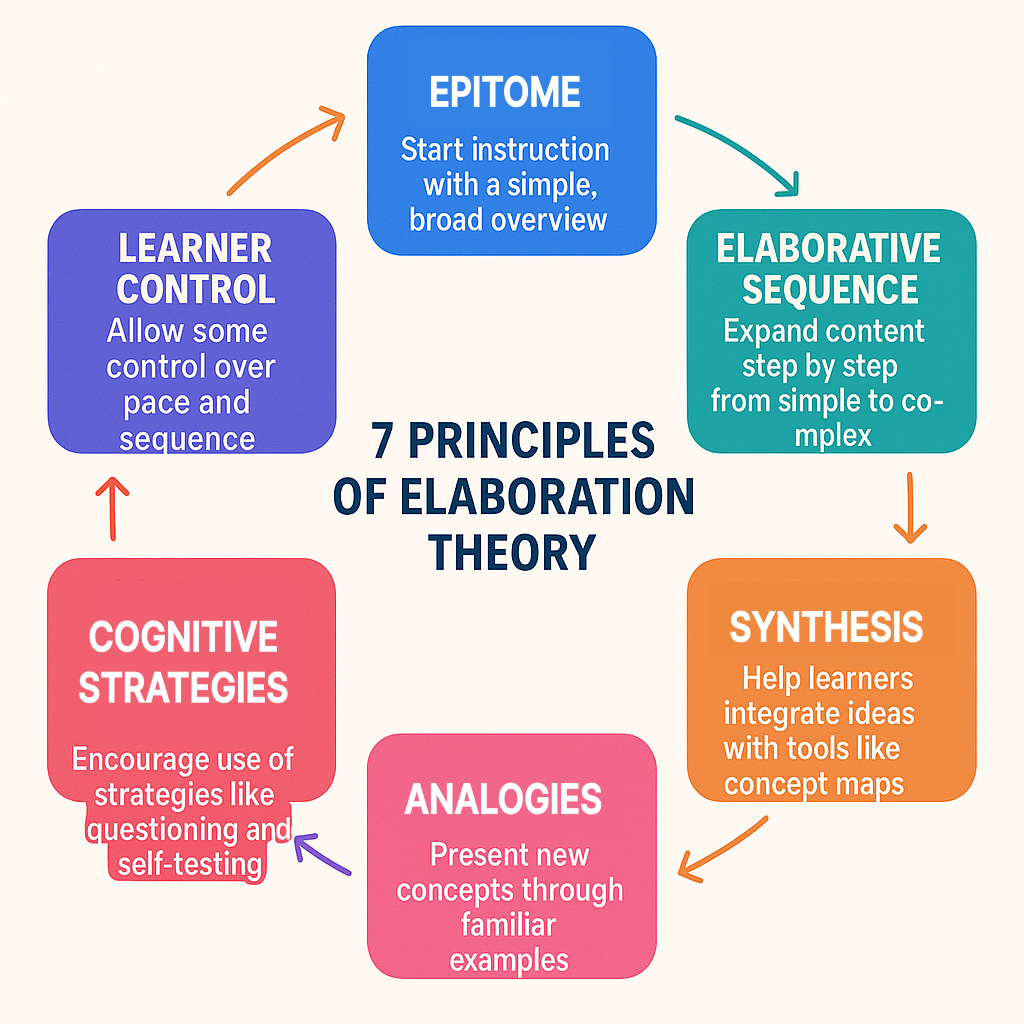

Designing instruction is rarely as simple as picking the right material. Teachers also have to think carefully about how to put that material in order so students can actually make sense of it. The way a lesson unfolds can mean the difference between clarity and confusion. Charles Reigeluth’s Elaboration Theory offers a systematic framework, advocating a progression that begins with the simplest representation of a subject and gradually advances toward more complex forms.

The main idea behind Reigeluth’s approach is simple: sequenced instruction. He believed that the sequence of content directly affects how well students understand, remember, and use what they’ve learned. To make this work, he suggested starting with what he called an epitome, which is a simplified version of the whole subject that gives learners a big-picture view. The epitome acts as a cognitive map, giving students a framework to organise everything else they will learn. From there, additional layers of detail and complexity are introduced.

Organising from Simple to Complex

Let’s revisit the epitome, which is the carefully chosen representation of the subject’s most essential concepts. In a biology course, an epitome could be the idea that “all living things are made of cells.” It’s broad, foundational, and simple enough for beginners. Once this is in place, the teacher can start layering details: the different types of cells, the role of organelles, and eventually the complex processes such as mitosis.

The simple-to-complex sequence ensures that learners build a mental model that can absorb additional complexity without collapsing under the weight of too much detail. This is especially important for domains where interconnections matter, such as science, mathematics, or language. The learner first grasps the structure, then gradually integrates finer distinctions and exceptions.

Synthesizing Ideas

Once the sequence is established, the next challenge is preventing fragmentation. Learners might understand individual parts but struggle to connect them. Synthesis addresses this by continually weaving new knowledge back into the overall framework. This reflects principles of schema theory in cognitive psychology. Educators help learners update their schemas by synthesising what they are teaching. This integration makes recall easier and understanding deeper. In practice, synthesis could take the form of comparative tables, concept maps and integrative discussions.

Analogies and Examples

Abstract knowledge becomes meaningful when tied to something familiar. A well-designed analogy or example functions as a cognitive bridge, mapping the unfamiliar onto the known. They work by leveraging transfer of learning, where learners project structures from a familiar domain onto a new one, which aids comprehension. However, they must be used carefully: an analogy that oversimplifies or introduces irrelevant associations can mislead. That’s why analogies should be grounded in the epitome so they reinforce rather than distract from the core structure that has been set up.

Cognitive Strategies and Learner’s Control

Cognitive strategies are techniques that learners use to process, store, and retrieve information more effectively. Examples include note-taking, self-questioning, organizing material into outlines or concept maps, and rehearsing information through practice. They are used to complement sequencing by helping students actively integrate each new layer of content into their mental framework. Instead of passively taking in information, learners are guided to construct meaning and engage in activities that help them reinforce connections on their own.

While Elaboration Theory provides a structured progression, not every learner needs the same level of detail at the same pace. Allowing students to give their input on material, explore optional examples, or adjust the pace of elaboration respects individual differences in readiness and interest.

Adiutor

Adiutor means "helper" - we do just that, by taking a load of your school administration and helping you focus on what matters most: the kids.

References

Ausubel, D. P. (1960). The use of advance organizers in the learning and retention of meaningful verbal material. Journal of Educational Psychology, 51(5), 267–272. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0046669

Reigeluth, C. M. (1979). Instructional-design theories and models: An overview of their current status (Vol. 1). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Reigeluth, C. M., & Stein, F. S. (1983). The elaboration theory of instruction. In C. M. Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional-design theories and models: An overview of their current status

Reigeluth, C. M. (1999). Instructional-design theories and models: A new paradigm of instructional theory (Vol. 2). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog1202_4

Sweller, J., van Merriënboer, J. J. G., & Paas, F. G. W. C. (1998). Cognitive architecture and instructional design. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022193728205

Thorndyke, P. W., & Hayes-Roth, B. (1979). The use of schemata in the acquisition and transfer of knowledge.