A Closer Look at Self-Determination Theory

We have all experienced that moment when we are so absorbed in what we’re doing that the rest of the world fades away. This kind of engagement feels different from simply “following instructions” or “getting the job done.”

We have all experienced that moment when we are so absorbed in what we’re doing that the rest of the world fades away. This kind of engagement feels different from simply “following instructions” or “getting the job done.” Self-Determination Theory (SDT), first outlined by psychologists Edward Deci and Richard Ryan, is one of the most well-established frameworks for explaining why this difference matters.

It suggests that the quality of motivation can be just as important as the amount. After asking “How motivated is this student?”, SDT encourages us to ask “What kind of motivation is driving them, and how sustainable is it?”. It also proposes that human beings are not passive recipients of incentives and instructions. Under certain conditions, people tend to take initiative, explore, and persist, even in the face of obstacles.

Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Motivation

Intrinsic motivation is often seen as the “gold standard” because it is driven by interest, enjoyment, or a sense of challenge for its own sake. It tends to foster deeper engagement, persistence, and creativity. For example, a student learning a new language because they love interacting with different people and cultures will stick with it longer and take more initiative than someone learning only to pass a requirement. However, studies remind us that intrinsic motivation is fragile and can be disrupted if the environment starts to feel controlling or if rewards are used in a way that shifts the focus from curiosity to performance. This is why excessive grading pressure can turn an eager learner into someone just aiming for a passing score.

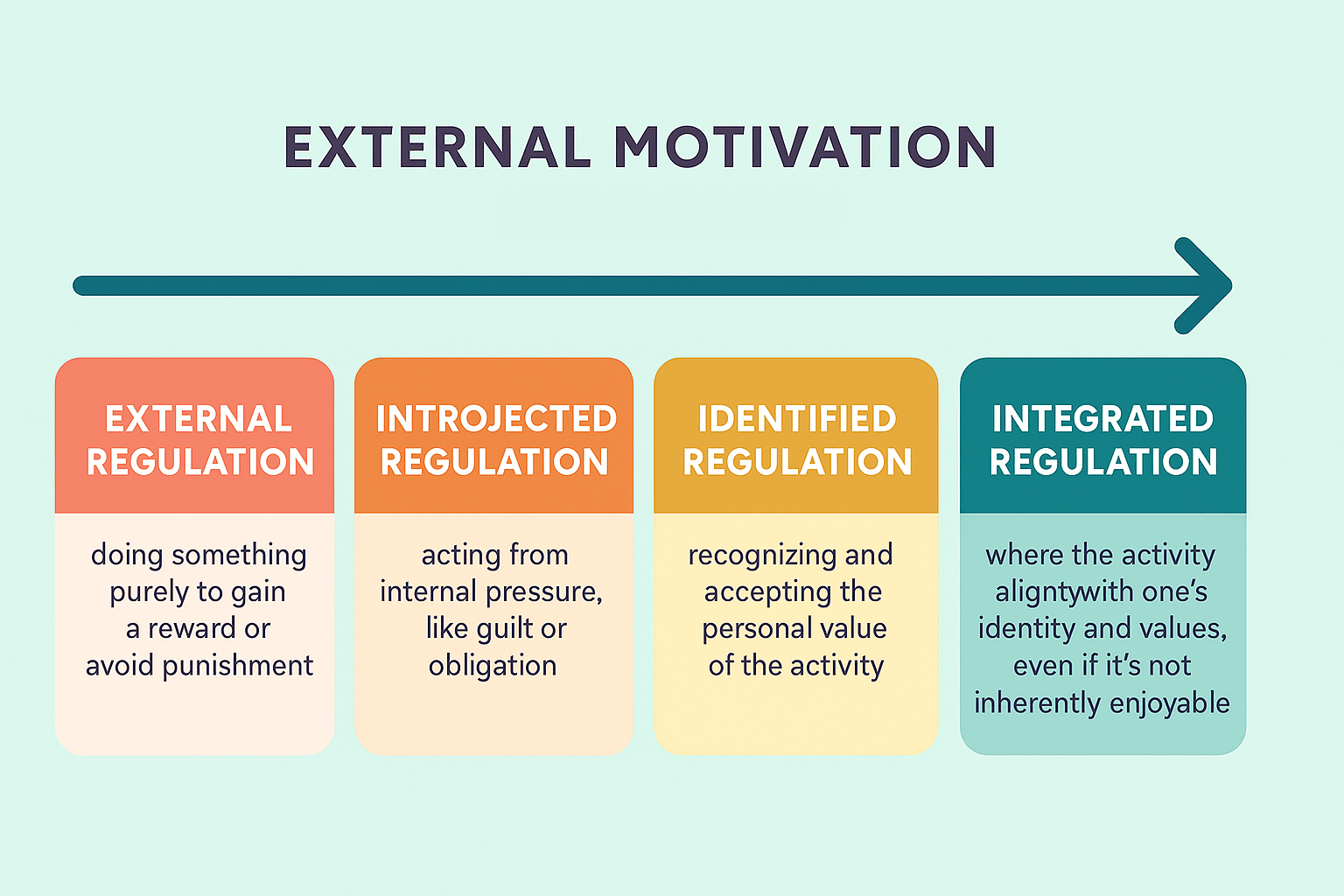

Extrinsic motivation, on the other hand, involves doing something for an external outcome (a grade, praise, a prize, or even to avoid punishment). While it’s sometimes seen as less “pure,” extrinsic motivation is not inherently negative.

The real challenge (and opportunity) is in helping extrinsic motivation move toward the more internalized end of the spectrum. This is especially important in education and parenting, where many necessary tasks (practicing math facts, following safety rules, studying for tests) are not inherently enjoyable.

A common mistake is assuming intrinsic motivation should always be the goal. In reality, some valuable skills may never be learned purely for enjoyment. The more practical aim is to ensure that even extrinsically motivated tasks are framed in ways that feel self-directed, meaningful, and connected to a larger purpose.

The Three Needs That Drive Motivation

Deci and Ryan identified three psychological needs that act almost like the “nutrients” of motivation. When they’re present, motivation tends to be deeper, more self-sustaining, and more resilient. On the other hand, when they’re missing, motivation often becomes fragile or dependent on external pressure.

These needs are:

- Autonomy – the sense that you have a meaningful say in what you’re doing. This is not the same as total freedom but rather feeling that your actions are self-endorsed rather than imposed.

- Competence – the experience of growing skill and capability, where challenges match your abilities and success feels attainable through effort.

- Relatedness – the feeling of being meaningfully connected to others, knowing that what you’re doing matters to people who matter to you.

Individually, each of these needs influences motivation. Together, they form the foundation for what SDT calls “self-determined” motivation, the kind of motivation that’s internalised and integrated into a person’s sense of self. They are basic psychological requirements for thriving in learning, work, and personal growth.

Adiutor

Adiutor means "helper" - we do just that, by taking a load of your school administration and helping you focus on what matters most: the kids.

References

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York: Guilford Press.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

Vansteenkiste, M., Ryan, R. M., & Soenens, B. (2020). Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motivation and Emotion, 44(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-019-09818-1